Key points

- Australian inflation looks to have peaked in the December quarter, which is later compared to our global peers.

- But, Australian prices lagged the initial rise in global inflation because wages growth in Australia has been lower compared to global counterparts, energy prices rose late in 2022 and flooding in eastern Australia resulted in additional upside pressure on food prices.

- The indicators around future inflation in Australia are pointing down rather than up. We expect a slowing in consumer prices to ~4% year on year to Dec-2023.

- The RBA is better off pausing after the February meeting to assess the impacts of prior rate rises at a time when the inflation background is looking better. Rate hikes are working – housing prices are falling, lending growth is negative, credit growth is softening and consumer spending is weakening. Further rate rises risk slowing the economy too much.

Introduction

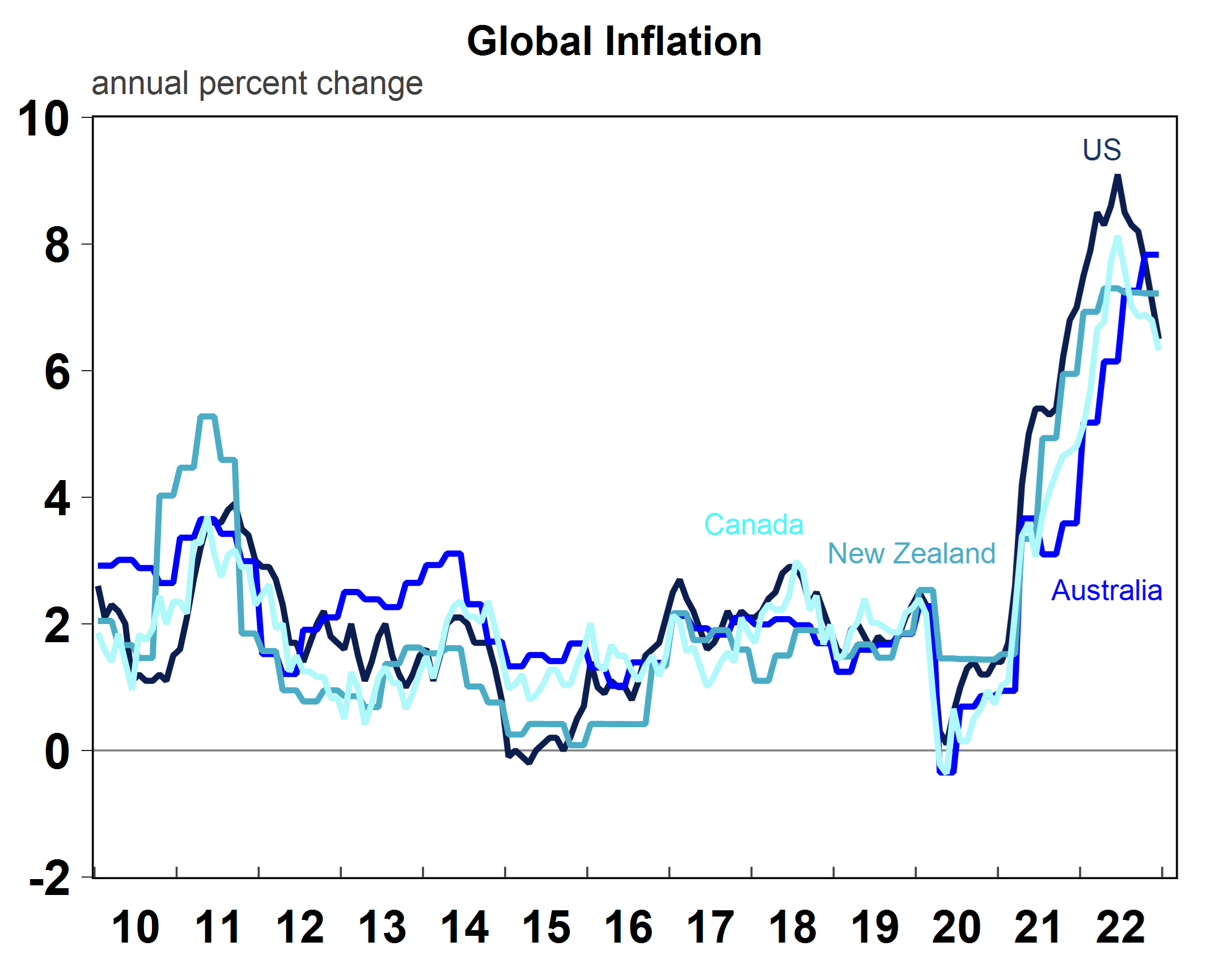

Throughout early 2022, inflation in Australia was running below most of our global peers. But, the data now shows that by late 2022, inflation peaked in many advanced economies including the US, Eurozone, Canada and Zealand and started to trend down. But in Australia, the latest December quarter inflation data showed that consumer prices rose further in the fourth quarter and reached a 32-year high of 7.8%. In this Econosights we look at why inflation in Australia was still rising late last year and outline three main factors that explain the lag in Australian inflation compared to the rest of the world.

Australian versus global inflation

In mid-2022, the Australian consumer price index was up by 6.1% over the year which was below our global peers, with US CPI at 9.1%, New Zealand ay 7.3% and Canada at 8.1%. But by December 2022, Australian CPI had risen to 7.8% compared to a slowing to 6.5% in the US, 7.2% in New Zealand and 6.3% in Canada (see the chart below). In 2022, the RBA lifted interest rates by 300 basis points, compared to the US Federal Reserve at +425 basis points, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand at 325 basis points (which started in late 2021) and the Bank of Canada at 400 basis points (also starting in late 2021). So, on the face of it, it would seem like the RBA needs to raise interest rates in line with these other central banks to also see inflation slow in Australia. But we don’t think this is necessary because just as Australian inflation lagged the rest of the world on the way up, it is also lagging on the way down. We see 3 main reasons that explain this difference.

Source: Macrobond, AMP

1. Wages growth in Australia is lower and will not reach the same levels as the US

The Australian labour market was in very good shape over 2022, with employment growth up by 3.4% over the year to December, the unemployment rate at 3.5% (close to its lowest level in 48 years) and the participation rate was at 66.6% in December (close to a record high). While the labour market is clearly very tight, wages growth has only lifted slowly and steadily, currently running at 3.1% over the year to the September quarter in 2022 (up from 2.4% earlier in the year). In contrast, wages growth has risen faster across our global peers, with US wages peaking at 6.7% year on year and 4.1% in New Zealand (see the chart below).

Source: Macrobond, AMP

Australian wages have lagged the rest of the world for a few reasons. Firstly, Australia has “inertia” in its wage system which means that it takes time for wages growth to adjust higher or lower. This is because around 60% of the workforce is on an award or enterprise bargaining agreements which need to be renegotiated and this process can be more rigid than employees who are on an individual agreement. Secondly, the supply of labour in the Australian workforce increased in line with demand since 2020, whereas the supply of workers in the US declined over this time.

The chart below looks at the difference in the demand and supply of employment, or the “jobs gap” in Australia and the US. This is a sign of the tightness of each labour market. In Australia, labour demand and supply moved into equilibrium in 2021/22 and weakened slightly by late 2022 (so labour demand is now below labour supply) while in the US, the jobs gap is firmly positive (labour demand is running well above labour supply). The US labour market was already much tighter compared to Australia before the pandemic and the additional demand that was added since the pandemic, along with a concurrent fall in labour supply led to wages growth breaking out strongly in the US. The US labour supply shrunk over the past two years (the participation rate has fallen by 1 percentage point since early 2021 from 63.3% to its current level of 62.3%) because many older workers (50+) left the labour force, taking an early retirement (due to health concerns and high savings allowing for early retirement). They are unlikely to all re-enter the workforce again which means that this lack of labour supply is permanent.

Source: BCA, Macrobond, AMP

We expect that Australian wages growth will reach a peak of around 3.75% by mid-year (the RBA expect 3.7%) which would still be in line with inflation target of 2-3% (if productivity growth is around 1-1.5%). There are no signs that Australian wages are going to break out to higher levels seen in the US, based on newly lodged and approved enterprise bargaining agreements and new salaries advertised (according to SEEK). Labour demand is also starting to soften, with job vacancies and hiring intentions slowing which will see employment growth weaken and the unemployment rate rise in 2023 – not the environment that is typically associated with high wages growth.

2. Australian electricity and gas prices increased late in 2022

Energy prices were rising in late 2021 across the US and Europe due to energy supply issues which was then exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. Australia was not as impacted by these issues initially because we are less reliant on international energy supply due to our own domestic sources of natural gas. However, our own domestic supply challenges (like coal plants being offline for maintenance) and the flow through of higher prices from the international market led to a rise in electricity and gas prices in the second half of 2022 (particularly in the December quarter as some state subsidies muted the rises in the September quarter), which was later compared to the rest of the world and also lined up with when many locked-in household energy bills were reset.

3. Flooding across the East coast of Australia led to additional food price inflation

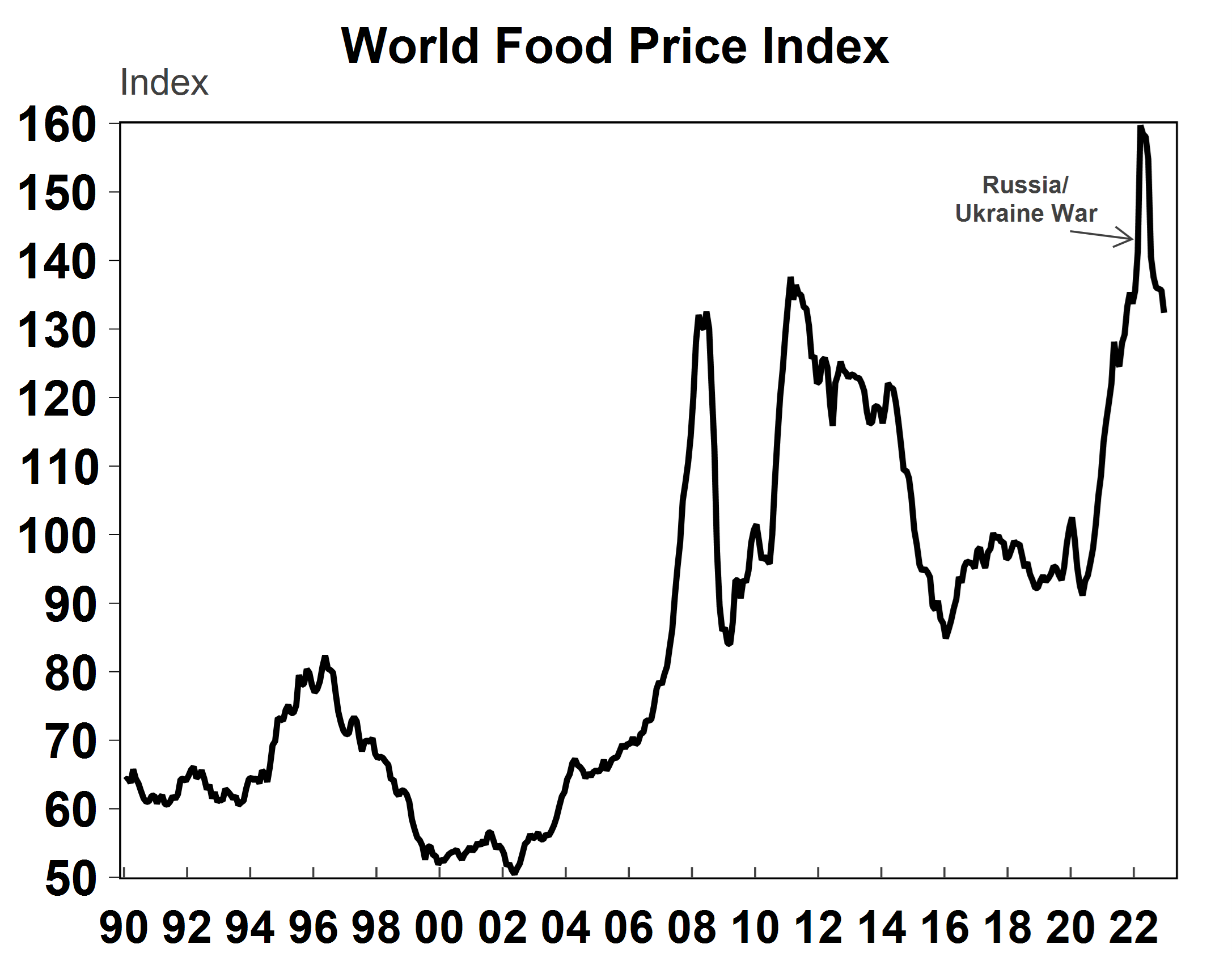

Global food inflation started lifting in 2021 from the global re-opening and ramped up through 2022 before slowing down slightly by the end of the year (see the chart below). US food prices were rising noticeability by late 2021 while in Australia, food price inflation picked up later in 2022 and was prolonged by multiple flooding disasters on the east coast of Australia which negatively impacted supply.

Source: Macrobond, AMP

Implications for investors

Australian consumer price inflation appears to have peaked in the December quarter (which the RBA also agree with). Australian inflation will start to trend down this year, but it will occur with a lag compared to our global peers who have already seen a peak in inflation. This is because wages growth in Australia has taken longer to rise and is still lifting (although there is no sign of a wages breakout), energy prices started rising later in Australia compared to our global peers and flooding events across the east coast of Australia will keep food prices elevated for longer.

Higher Australian inflation data compared to our global peers should not be taken as a signal that the RBA has much more work to do to get inflation down. Most signals are pointing to lower, not higher inflation in coming months – commodity prices are declining, transport costs are falling, rental growth increases are slowing and consumer demand for discretionary spending is weakening which will alleviate inflationary pressures. We expect annual consumer price inflation to slow to ~4% year on year by December.

Last year, the risk was that inflation would become unanchored which justified significant RBA rate hikes. While inflation was still high in late 2022, inflation expectations have been trending down since mid-2022. Another 0.25% interest rate rise is likely at the RBA’s February meeting, but the risk is that further rate rises slow the economy too much at a time when the inflation backdrop looks better. The RBA is better off pausing after its February meeting to assess the impacts of its previous tightening.

Weekly market update 15-11-2024

15 November 2024 | Blog Global share markets were messy over the last week, not helped by the ongoing rise in bond yields and a wind back in Fed rate cut expectations after some elevated US inflation data and slightly hawkish comments from Fed chair Powell. Read more

Oliver's insights - staying focused as an investor

12 November 2024 | Blog Dr Shane Oliver suggests five ways to help manage the noise and stay focussed as an investor with the changes in the macro enviroment. Read more

Weekly market update 08-11-2024

08 November 2024 | Blog It was all about the US Presidential election this week. Despite concerns that the election outcome would be extremely close, the Republican victory was stronger than the polls and betting markets were suggesting into the lead up. Read moreWhat you need to know

While every care has been taken in the preparation of this article, neither National Mutual Funds Management Ltd (ABN 32 006 787 720, AFSL 234652) (NMFM), AMP Limited ABN 49 079 354 519 nor any other member of the AMP Group (AMP) makes any representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This document has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this document, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This article is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided and must not be provided to any other person or entity without the express written consent AMP. This article is not intended for distribution or use in any jurisdiction where it would be contrary to applicable laws, regulations or directives and does not constitute a recommendation, offer, solicitation or invitation to invest.

The information on this page was current on the date the page was published. For up-to-date information, we refer you to the relevant product disclosure statement, target market determination and product updates available at amp.com.au.